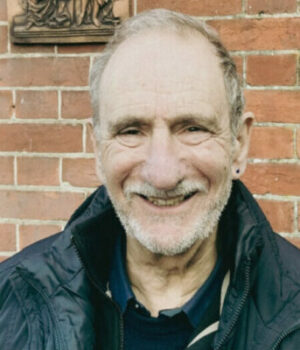

Interview With Richard Sylvester Discussing his Spiritual Journey and Non-Duality (recorded 2020)

Richard Sylvester leads meetings and publishes books discussing non-duality.

In our very first published interview, Richard kindly took the time with us to talk through his journey of spiritual seeking over thirty years. He also discusses how he approaches talking about non-duality.

Find out more about Richard at www.RichardSylvester.com

Interview Transcript

Louis: Hi, I’m Louis Allport, and today I’m speaking with Richard Sylvester. And Richard leads meetings, and also publishes books about non duality. And today we’re going to be speaking about his personal journey, so to speak. And how he communicates the ideas, or his perspective on non duality these days, and why he chooses to communicate it that way. And also some of the common questions and some of the common responses he experiences from people at meetings, and by email and elsewhere. So hi, Richard, and thanks very much for your time today.

Richard: Hello. You’re welcome.

Louis: Okay. I guess I’ll keep my questions relatively brief or my introduction to sections of this interview relatively brief. But would you say it’s true or accurate that, like many of us, or maybe most of us in different ways, you were looking for answers in some form. Would that be true?

Richard: Oh, yes, absolutely. I was a classic seeker for probably 30 years or maybe more. Looking for… I don’t know… the secret of life, enlightenment, whatever. There was always the feeling that there was just something going on, which clearly I didn’t understand. And there was the feeling that somewhere, someone or some others did understand. So yes, I was a classic seeker.

Louis: Can I ask what age that started? And was it initiated by anything in particular, or did it, I guess, maybe pop into your head at some point?

Richard: I can give very precise answers to both of those questions. I would say it started when I was in my late twenties. And it was probably initiated by my first acid trip, which had a fairly staggering effect on my mind, my experience, whatever you want to call it. I sometimes compare that acid trip to being kicked in the head by a mule. It seemed to reveal to me that reality as I experienced it was just one possible version of reality and there might be many other possible versions.

So it got me interested in looking at a whole range of possibilities that I’d never looked at before. And then at a certain point after that… I can’t pinpoint a clear cause and effect here, but I’m pretty sure there was one nevertheless… at some point after that I found myself handing a large sum of money over to the Transcendental Meditation (TM) organization to learn TM. So that really was the second thing that was a sort of revelation to me. After that I was up and running down the path of spirituality, I would say.

Louis: So it happened at 29? Was it in this country, or were you traveling, or…?

Richard: Well, I was just leading my very ordinary life. I wasn’t traveling exotically, I wasn’t halfway up a Himalaya, I was a lecturer in a London College. There’s quite a lot of autobiographical detail I could go into but I won’t. I think I was at a fairly low point in my life. I’d had a relationship breakup, that sort of thing. And somebody I knew – one of my students actually – was talking to me about Transcendental Meditation.

One of the things about that was that a few years before I’d had a conversation with someone where I was really mocking it. So I was very much not open at all, and not available at all to those kinds of ideas and those kinds of practices. And then, as I said, there was this kick in the head from a mule from this acid trip and then a descent into a certain amount of unhappiness. And then just the feeling “Well, here’s somebody talking to me about TM, and it might just be the answer”.

So I went along and handed over a very large sum of money and I think some fruit and some flowers – I think they were also part of the ‘fee’. I was feeling very foolish as I did so. And before I was halfway into the initiation, I was pretty sure that I’d wasted my money. I was feeling very foolish – “Oh, what am I doing here?” But then I actually started the practice. And I was just one of those people that the practice had an enormous effect on, which I couldn’t deny. After that, I think I was just hooked.

I was looking for a way out of my misery, which I think is what brings many people to this kind of ‘path’, let’s call it. I had dabbled a little bit philosophically. I’d read some Buddhist books, I’d read some stuff on Zen. I’d even tried a little bit of Buddhist meditation on my own at home. I hadn’t got anywhere with any of that. It all seemed very dry and unproductive.

So obviously there was a little bit of openness there already before that, but I would still say the TM initiation was like a revelation. It really was an initiation into the possibility of a different way of being. And so I became very enthusiastic about that and this carried on for me for some time. Even if things didn’t seem to go well, I became a rather fanatical meditator. And even when I went through periods where I didn’t seem to be getting anything from it, I still kept going because I’d been so enthused by my original response to it.

It’s a complete mystery why that should be, because I also became a TM bore to my friends after that – because of course I started talking to them about it and encouraging them to learn it as well. A few of my friends did go off and they paid large sums of money as well. But it didn’t really take with any of them. I just assumed everybody would get the same effect that I had, but it turned out not to be the case. So they didn’t feel they got much from it and they gave it up pretty quickly. Whereas I went on, fairly fanatically I would say. I had to have my meditation twice a day whatever the circumstances.

I went on quite fanatically, expecting that I would go on for a very, very long time. But then unexpectedly I came across a guru and something inside me just went, “Ah, this is now the one for you, Richard.” So having been incredibly keen on Transcendental Meditation I then abandoned it, probably after about three years. I abandoned it rather abruptly and went off dancing as it were with these other meditation techniques from this very charismatic guru.

Louis: Okay. So, you started with the TM introductory course if that’s right, which is I think a few weeks, and then twice a day for three years. Was it twice a day for 20 minutes a day, is that right? Or can it be any length of time?

Richard: Oh, absolutely not. You have to follow the rules very carefully. Twice a day, 20 minutes a time. And I was going off on TM retreats – I can’t remember how long, maybe a week or a couple of weeks at a time. I did what they call their Science of Creative Intelligence course as well. This is a kind of induction – I suppose it’s an induction into yogic philosophy, but yogic philosophy masquerading as science. Or perhaps it’s the other way around – perhaps it’s science masquerading as yogic philosophy. I’m not sure.

So I was very enthusiastic. I put a lot of energy into it. I even thought about training to become a TM teacher. Then that in its turn suddenly fell apart when I heard about this guru. And rather ironically, I heard about the guru when I was actually on a TM retreat. The conversation I overheard was between two much more experienced TM-ers than I was and they were actually talking about how awful this guru was and how dangerous and how no one must ever go near him. But there was something about what they said… I just… I don’t know what happened. This energy came up in me and I thought “I’ve got to go and see this man”.

I was living in London so I had plenty of opportunity to go and frolic amongst spiritual things if I wanted to. I had looked into various other things. I’d gone to the first festivals for Mind Body and Spirit – I think they were at Earls Court – huge affairs. But there was something about… something that was said about this new guru who had come on the scene fairly recently. I can’t explain it but I think a lot of people with histories in the spiritual world will have had similar experiences… that energies just suddenly erupt to do certain things. So that’s what happened with me.

Louis: Did you suddenly lose interest in TM or did it just stop working?

Richard: It certainly didn’t stop working, the practice. No, I was still meditating. But I lost interest in it as an organization. I lost any interest that I’d had in training to be a teacher. And I couldn’t wait to scamper off and learn new meditation techniques from this new guru. I did. I went and learnt them and they were… they’re very similar to TM in a way. The practices were not a million miles apart from TM, but I found them incredibly effective and I sort of fell in love with this new organization.

It was a very new organization. One of the things that hooked me was that because it was new, it was creating opportunities for people to train as teachers in a very simple way. I’d already been thinking (I think quite insanely) of giving up my very well paid very interesting professional job and going off to Switzerland to train as a TM teacher. I think it would have been a complete disaster if I had done this.

Then suddenly here I am in this new organization and they’re offering me the chance to train as a teacher at very little cost to myself. By “cost” I mean very little effort. In other words I didn’t have to give up my job, I didn’t have to go to another country to do it, I could just go on living my normal life. And I could add on to that, as an adjunct as it were, becoming a teacher for this new organization. That suited me down to the ground. And I loved the techniques. I thoroughly believed in them. I thought they could bring huge benefits to people.

Louis: So you say the technique is fairly similar to TM in some ways?

Richard: Yes. They had a mantra meditation technique which is quite similar to TM. But they also had other techniques to add on to that. That was exciting for a seeker. So they also taught Tratak, a candle meditation, which was also a lovely technique. Then later on they taught a mandala meditation, which was also lovely. And in groups on retreats we chanted a lot and meditated to the sound of a huge Tibetan gong.

It was all lovely but the techniques… for me, again, they just seemed to (not always but sometimes) take me to very deep places. I was very happy with this. Also I now had a little position in the organization because first I was a teacher and then I became a senior teacher. So it was all going very well.

I was very, very happy. And just to add to that I suppose I should throw in at this moment that we also happened to believe that our guru was the Avatar of the New Age – which made it very exciting indeed. Now, anybody of my age who took an interest in such things would probably know immediately that around that time there were at least three or four – or maybe five or six or more – gurus who were being presented by their devotees as the Avatar, the one and only Avatar, of the New Age.

But of course we knew that we had the authentic one and everybody else was mistaken about theirs. It was a little like being a religious convert with considerable zeal whilst continuing my day-to-day life and my profession. Even better, the guru would come over to England in the college holidays to run retreats. I would go on those, so I didn’t have to sell everything I owned and walk up a mountain in the Himalayas in order to sit at his feet. I could go and sit at his feet in a comfortable hall at the University of Keele in the summer holidays instead. So it was kind of a path for devoted devotees, but quite lazy devotees as well.

We didn’t even have to become vegetarian, which was wonderful. I mention that because at a certain point in this story I was offered the chance of being initiated by a much more traditional Indian guru. But I was told almost at the last minute that I’d have to become a vegetarian, so I decided against that one.

Louis: Oh okay. So how long were you involved with that?

Richard: I have to work this out. It wasn’t very long. I think my best guess is about three years, or it could have been a bit longer. Then the whole thing just came crashing down. There was an almighty scandal – as there often is with such groups. The whole thing just literally collapsed in a very short period of time.

Louis: Did you feel a little bit adrift at that point?

Richard: No, no! I felt absolutely and totally adrift! I felt completely adrift! It was a horrible experience! Because for at least three years, I think it was, we’d invested so much love and energy into this adventure. And of course by then a lot of my social contacts and my friends were members of this group. It was a large and seemingly very functional family and very fulfilling in all sorts of ways. Then one hideous evening it all came crashing down. It was a terrible, terrible shock. It took a long time to recover from that.

Louis: So when that happened, were you continuing with meditation? Or did you stop everything? Or were you looking for something else?

Richard: I stopped teaching for the guru. I stopped teaching meditation. I left the organization – what little bit of the organization was left. Most people – most of the teachers – left. But a few carried on. So the organization did go on but in a much smaller way. I never really joined an organization after that. I never really committed to any teacher or organization after that but I went on meditating and I kept that up for many years – many, many years.

Louis: So could you describe the months or years after that? What happened, and where did you end up?

Richard: Oh, gosh! I could do the thirty second version of that or the four or five hour version of it. Let me try to think of something in between. I went on seeking I suppose, in the sense that I did look into other teachers, I did look into other organizations. I flirted with at least three or four different forms of Buddhism, different schools. But one of the ways I put it is that it’s as if that guru experience gave me an inoculation against gurus and teachers in the future. So nothing in me ever wanted to commit to a particular teacher, a particular human being or a particular path after that.

I went on doing a daily practice. I think doing a daily practice is quite a good idea for all sorts of reasons. So I went on doing a daily practice and I went on … I’m going to use the word “investigating”, by hanging out in various groups, going on a few retreats and things like that. But nothing of that nature ever really stuck with me again. But the main thing that happened after that was that I became very interested in what I would call Western psychotherapeutic paths, rather than Eastern spiritual paths. So I started taking retreats and going on courses in the Western psychotherapeutic schools and techniques.

I did a wide range of those, but I was always mostly attracted to the ones that had what might be called a “transpersonal” element. So even there, as I got more and more into the Western paths, it was the ones with more openness to spiritual paths. I spent a few years – one or two, possibly three… I can’t really remember, but a few years – doing some trainings in very, very heavy encounter style psychotherapeutic paths.

That sort of thing had come over here from the Esalen Institute in Big Sur in America and they were pretty kamikaze in a way. Once you’d entered the hall and signed your agreement and signed away your rights as a human being, you never quite knew to what extent you might get beaten up and battered psychologically. But I found all of that very exciting and useful and fulfilling. So I did that for a while.

I was actually involved with an organization which only existed for a short period of time. But I think it was a wonderful organization at the time, because it took these very confrontative kinds of Western group-psychotherapeutic encounter techniques and it combined them with a spiritual approach and with meditation. For me that was very powerful. And I suppose that went on for – I can’t really remember – maybe two, three or four years.

After that I got into using this stuff professionally myself. Because I worked in education, I worked in colleges, I got opportunities to start teaching it – both in the psychological and counselling fields and also a little bit in the spiritual fields as well. I was introducing meditation courses and things like that into my teaching work.

Louis: So those few years, you felt they were beneficial, mentally or emotionally in some ways?

Richard: Absolutely. That’s very strongly what I felt at the time.

Louis: If you don’t mind me just coming back to this. I’m just trying to track this on an age basis, because it’s interesting to me and maybe interesting to other people. So it started at 29. You said, three years in TM, three years with the guru, a few years of this. So this takes us to maybe 40, early 40s. Is that right?

Richard: Yes, that sounds about right. Yes, yes. Approximately.

Louis: So maybe one question is what were you still looking for specifically? Did you have a feeling of dissatisfaction? Or you felt this isn’t it, this isn’t it? And you were kind of looking around the corner for something else?

Richard: Yes, I think that’s a good way of putting it. I think it’s fairly obvious from everything I’ve described so far that I was very much on a progressive path. I believed in the progressive path, though obviously by now I didn’t see myself as being on any one specific path.

But that was also in the spirit of the time because we’d become very eclectic by then. So this is what a lot of us were doing. We were going to one guru here and another guru there and trying this technique maybe for a year or two, and a different technique for another year or two. And combining this bit of Buddhism with that bit of yogic philosophy with perhaps a bit of Christianity or something like that.

It was very much… a phrase that’s been used for this approach, and it’s used derogatorily, is a “Pick and Mix” culture. But I don’t take that as derogatory at all. I think that’s an incredibly sensible thing to do. And even if it isn’t sensible it can be fun and entertaining. So I embrace that kind of “pick and mix” approach and I have no regrets about it.

But the other part of what you said, the other part of your question? Yes, underlying that, definitely, there was still the feeling which I think is summed up by quite a few people in the phrase “This isn’t it”. So I was still searching. I didn’t know what the hell I was searching for but the one thing I knew was “This, isn’t it”. This wasn’t it. I hadn’t found it. I didn’t know what it was that I was looking for but I did know that I hadn’t found it. In other words, there was that underlying sense of dissatisfaction, unhappiness, lack, however we want to put it, which is a common cause of keeping us seeking.

Louis: Dissatisfaction is probably true for everyone in life. But for the seekers, as you say, it’s meant to be… many of us think about it, if not most of us think about it as progressive, something progressive. As in this step, then this step, and then this step, and I’m getting somewhere. And we’re not quite there yet so do something else, not quite there yet do something else. I’m sure, I’m very sure, I’ve been guilty of that, if not continue to be guilty of that. And people I know. And that is probably just part of being human.

Richard: I think it is The Human Condition. In some ways it can lay us open to very interesting and very exciting and colorful experiences. But it is absolutely the human condition, of course.

Louis: What was the next… what happened beyond that? You are going to… you’re taking part in this and you have this sense of dissatisfaction, or this isn’t it. Where did that lead you? I mean, either consciously or unconsciously, where did that lead you to?

Richard: Well, there was a bizarre coincidence or synchronicity one day. At some point in all of this I got invited to a meeting of Tony Parsons. This was a long time ago when he was holding his meetings in the house of some people I knew and had contacts with. So I got invited to this meeting and I went along and I listened to him.

I liked Tony as a person but I wasn’t remotely interested in what he said, partly because I didn’t really understand much – if anything – of what he said. I met a few nice people, had a cup of tea and a cake, went home and thought “Well, I don’t want to go back to that again…. but a nice afternoon out”.

Then at some point after that – I couldn’t tell you when, it could have been a year later, it could have been two years later – there was this bizarre coincidence or synchronicity. Without boring you with the details, what happened was that two different people who did not know each other both invited me to another Tony Parsons meeting within about three days of each other.

One of them said “Oh, you’re probably not interested but Tony’s giving a meeting in Hampstead on Saturday. It would be nice if you felt like coming”. And I thought to myself, “Yeah, I certainly won’t feel like coming.” And then literally two or three days later I was with another group of people and talking to somebody I hadn’t met before. She was talking about Tony and she mentioned the same thing. “There’s a meeting on Saturday, why don’t you come along?”

The hook for me at that point, and what she said made it clear, was that there’d probably be a fun group of people who’d go over to the bar cafe afterwards and they’d sit around and they’d drink and chat. She made it sound like quite a nice social occasion. So I thought “Oh well, why not?”

So I found my feet taking me up the hill in Hampstead to a second Tony meeting, the meeting that I thought I would never want to go to again. And I cannot explain it – I sat through the meeting, I still probably understood almost nothing of what was being said, but this time there was something about it that just got me. It hooked me.

And there was a nice group of people that went over to the bar cafe afterwards and sat around and drank and had a pleasant conversation. The combination of those two things just made me want to go back. So there I was, month after month. My feet were walking themselves up Heath Street in Hampstead to listen to Tony and to drink with a nice bunch of people afterwards.

And as time went by, I don’t know – I wouldn’t really say that I understood much. But perhaps I began to understand just enough to start asking questions. So then I went through a period of remorselessly asking question after question after question. I must have been a complete pain actually.

I’m sure there were people in that audience sitting there thinking, “Oh God, I wish he’d shut up.” But I asked question after question. Many of them were about death, I remember. For some reason I particularly wanted answers to questions about death. So that was the next thing that happened. I got hooked. I got hooked on non-duality.

Louis: When you say you got hooked, did it manifest as mental curiosity or was it something else? Or did you just find yourself attracted to it, but you weren’t entirely sure why?

Richard: Probably all of that. There was definitely mental curiosity – obviously, from the number of questions I was asking. There was definitely something about the “energy”. Please don’t ask me to define what I mean by that word – it’ll just have to do. There was definitely something about the energy which I liked.

It was a nice bunch of people – there was something about the social aspects of it I liked. And remember I’d been quite an important person in the guru’s movement. I think we had 20 senior teachers in this country and I was one of them. What a wonderful position! I’d lost all that. I’d just become a kind of spiritual nobody. But here I was back with a nice bunch of people – and then I was offered this position as Assistant Tea Boy. That really locked me into it. So there I was. I liked the energy, I liked the questioning and the answers, I liked the people – they seemed to be very amiable.

There seemed to be… I think this is important actually… there seemed to be a real… this is just occurring to me… there seemed to be a real air of freedom and permission and even permissiveness around this. I’d spent a lot of time hanging around spiritual organizations – there’s a lot of morality and virtue and even moralism, and assumptions about sticking to rules and disapproval of the breaking of rules. A lot of spiritual organizations can be quite uptight. Some spiritual organizations can be unbelievably uptight, almost neo-fascist. I shall probably regret using that term, but never mind.

So there was this feeling of relief and relaxation, just such freedom hanging around these meetings. And as I’ve said, then I was enticed in with this magnificent opportunity to become an assistant tea pourer. I was part of the crew then so I really couldn’t leave after that.

Obviously it will sound as if I’m making light of this. In a way I am, deliberately, because there was a lightness about it. And that’s part of what was so attractive. Because spiritual seeking can be so damn heavy, so damn serious. My God! If you put a foot wrong then you might be cursed with 30 extra reincarnations. And it was just delightful not to have that.

I remember reading an article years ago, by… I think her name is Mariana Caplan. It was in some enlightenment or spiritual magazine. It just seemed so heavy to me. It seemed to be suggesting that almost everything that we did as seekers was wrong. It was wrong, wrong, wrong! Everything! You couldn’t move without putting a foot wrong! So you’d better find yourself that wonderful… I don’t know… that wonderful Buddhist monk or whoever it might be … the Buddhist saint, or whoever. Because without that, everything you were doing, you were just deceiving yourself, fooling yourself. You know, “spiritual stupidity” was rife everywhere.

And I really hated that. I really revolted against it. In fact I wrote a letter to the magazine saying that I smelt the whiff of spiritual fascism from this article. To be in the atmosphere around Tony in Hampstead, there was none of that – absolutely none of that. It just felt wonderfully freeing.

Later on I came across a few words about Advaita that I hadn’t met at that time. I can’t remember who wrote or said them but they were “There’s something of the breath of freedom blowing through Advaita”. As soon as I read those words, I thought, “Yes! Absolutely!” That’s something that on some level, without my knowing it, was part of what I recognized when I became hooked on those meetings in Hampstead. It’s the breath of freedom. No rules, no guidance, no path, no techniques. Just freedom.

I can’t explain it. And I don’t think there’s any point in trying to explain it rationally, how something about that hooked me. There were obviously things about it that I liked, which I can rationalize and have done. I liked the people, I liked the socializing, there was quite a lot of laughter as well and I liked that and the informality. But obviously there was something above and beyond that which can’t be put into words. And it can’t be put into thought. I could just use the word “energy”, which is almost meaningless. But that’s about as far as I could go. Something about the energy of it really hooked me and I just wanted more of that.

I think in a way there was something significant about that energy. I wanted more of that, even though on a mind level I didn’t really understand very much of what was going on. You know Ramana Maharshi’s phrase? It’s a very famous phrase:- “Your head is in the tiger’s mouth.” I think that’s probably the best way that I can put it. For some reason or no reason, and certainly inexplicably, that second time that I went back and then got hooked my head was in the tiger’s mouth.

Louis: So how did the years after that take shape?

Richard: The reason I’m hesitating is because this is the point at which language breaks down. We have to use language but it’s so inadequate. So… these are meaningless terms… but what I would say is that after… I think as I remember after a year there was a … I’m going to use the phrase “partial breakthrough” because that’s maybe the conventional way of describing something like this. I think many people will know what I’m talking about. And the word “breakthrough” isn’t that appropriate in a way, but there was a kind of partial breakthrough into “Ah, yes, this is what this is all about.”

So it began to make sense. And when I say “it began to make sense”, I don’t necessarily mean intellectually. It just began to make sense on a kind of total level. The “mind, body, spirit” level, whatever you want to call it. Of course these words begin to become redundant when we’re talking about Advaita.

Then I think another year after that there was another breakthrough. Then it was kind of “Oh, yes, that’s it. That’s all it is. This is what’s been puzzling me the whole time I’ve been coming up to Hampstead … but it’s actually what’s been puzzling me all my life.” Certainly it was what had been puzzling me ever since I became consciously involved in spiritual matters, when I started TM, or even before that when I started reading Buddhist texts and Ram Dass and people like that. “Oh yes, this is what it’s all about. Oh Christ, isn’t it simple?”

So there were those two breakthroughs. And then – some people listening to this will absolutely know what I mean by this, maybe others won’t – then it was all over. It’s just over. It’s game over. There’s nothing left after that, except for life happening.

Louis: So we’ve got to the point where you may be starting to… I’m sure you find this in meetings and also in your books, is you’re explaining things which people might have a strong reaction to, or don’t understand at all, or they just get confused. And maybe they stay interested, maybe they don’t stay interested. So from what you’ve just said, how have you found a good way to communicate it? Or attempt to communicate it in a way that people can access? If that’s a coherent question.

Richard: Yes, it’s a coherent question. I don’t know if I can answer it in the way that you put it, which isn’t a criticism of the question at all. Let me try this way. Some people, it’s kind of … it’s all over with them. But there isn’t an urge in them to communicate it to other people. They just don’t have that kind of personality. So they go off and continue to be a sheep farmer or a bus driver or whatever it might be.

But I had always been professionally a communicator. I have that kind of personality or energy. I was a lecturer all my professional life. So it was pretty natural for me to want to both write about this and talk about it. It’s just my nature, my personality. It would have felt a bit strange to me not to do that.

Because all through my life, whenever I’ve had an enthusiasm for something, I wanted to communicate it. And I was lucky to have been able to earn my living in a profession where I was able to do that. So whether it was Shakespearean tragedy or non-duality, it’s just natural for me to want to write, want to give talks and want to answer questions. So that’s what I started doing. But for me, the question would have been – if I hadn’t done that, why would I not have been doing that, when my whole personality leans to that kind of process, communicating about the things I’m interested in to other people.

Louis: What you do with meetings and through books is you share your perspective, would you say that’s right?

Richard: I’m slightly reluctant to concur that it’s my perspective, although obviously in a sense it is because I have a certain character. So I share in the way in which that character is constructed. I think I just try to share (hopelessly, because it’s always hopeless, this sharing) an understanding of this, a feel for this. That’s all I can say.

I don’t think I have a perspective. As I’m saying that, I can hear cries of outrage possibly from some people and maybe those cries of outrage might be justified, I don’t know. But I don’t know that I have a perspective. I’m just trying to communicate that which cannot be communicated. It was Alan Watts, I think, who said he was trying to eff the ineffable. So that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to eff the ineffable.

Louis: Okay, because what you’ve just said, I know in people who are new to this topic, or unfamiliar with this topic, or mildly interested, this is where they often have a lot of confusion or strong reactions. And this is often where people seem to get lost. I mean, as you say in your journey, even though you were confused, you stayed interested because something was taking you back.

And maybe a similar sort of feeling or similar sort of motivation, whatever there may be, is what gets a lot of people over this stage of being utterly confused and maybe even having quite strong feelings about it. Because I’ve seen people angry or upset about what Tony says, for example. I think that’s happened to you as well. I remember in one of your YouTube videos you mentioned you’ve had strong reactions as well. I guess it can come across as nihilistic or fatalistic, as ultimately there’s no hope, and personalities or human beings will almost invariably have a strong reaction to that.

Richard: Yes, I think there’s little I can say about that other than “Yes, it can sound nihilistic.” And it absolutely isn’t! It’s a million miles from nihilism! It can sound solipsistic, and it isn’t. It’s a million miles from solipsism.

And certainly I think the thing that people have the strongest reactions to is the suggestion… as soon as we tread on the thin ice of free will, people tend to have very, very strong reactions to that. People do not like having even the concept of free will challenged… a certain number of people get very angry about that. And of course, the non-existence of the self… that’s the other thing that can get people quite agitated.

My own way of dealing with that is to try to talk about this as little as possible, unless it’s to a group of people I know are interested in it. So if my friends or somebody in a pub starts asking me what it is I give talks on, I tend to become extremely evasive and I try not to tell them. I become as vague as possible, because in my experience, it’s both… it’s futile and it can be quite aggravating to have a conversation with somebody about this. They have no feel for what it’s about, no desire to know what it’s about, but they do want to have a fight with you about the idea that there’s no self or that there’s no free will.

So I just find it’s best to avoid those situations. By the way, I’ve talked to and had emails from a lot of other people who’ve experienced the same thing. When people get into non-duality, there can be a period of excessive enthusiasm where they want to talk to all their friends about it. And quite often they discover very quickly that’s not a great thing to do. I don’t give advice, but if I did give advice I’d say “Just be evasive. Be as evasive as possible.” If one of your friends wants to know what you’re doing on the first Saturday of the month, unless you get a sense that they really are genuinely interested and might have a feel for it, just be as evasive as possible.

I had somebody who used to come to my meetings very regularly… used to – let’s not be polite about it – used to frankly have to lie to their partner about where they were going. And they were not the only person that I’ve heard that from. I remember having a conversation with them one day, and basically the feeling seemed to be that it would have been more okay if they’d been going to a brothel or an opium den or casino, than if they were going to a non-duality talk.

The other thing I say is, “Well, it’s a bit like Buddhism, but not quite”. That usually shuts people up.

One of the most terrifying sentences anyone can say to me is – if it’s a friend of mine and they say to me “Oh, I’m going to come along to one of your meetings soon, Richard”. I don’t want to hear that! Not from a friend! Well, if it’s a friend who’s interested in non-duality, yes. But it usually isn’t.

And yes, of course the idea that “I” don’t have control over something called “my life” is an absolute insult to the ego. It’s a terrible thing to say to the ego.

Even worse than that, I wouldn’t say that there’s a “you” who has no control over your actions. That’s what people hear and that’s what people say – the average person in the pub is probably so ready to fight me or anybody else who says that, because that’s what they hear. What they hear is “There’s a you there, but it’s helpless, it has no control.” That’s not really what’s being said. What’s being said is not “There’s a you but it has no control.” What’s being said is “There is no control, control is irrelevant, because there is no you.”

That might sound like I’m splitting hairs but believe me I’m not. There’s a zillion miles between the suggestion that “You exist but you’re powerless” (which is not what I’m saying), and “There’s no choice, there’s no free will, de-da de-da de-da, because the ‘you’ does not exist.”

Remember The Great Mantra. I think it was in my first very short book. The Great Mantra was “Hopeless, helpless and meaningless.” That might be an antidote to hope raising its ugly head.

The “Why” questions are very natural for the mind, particularly the mind of the individual who feels separate. But the “Why” questions can only ever be answered with a story. And it can never be known. In actuality, it can never be known. “Why are my feet taking me up the hill to Hampstead to listen to a talk on non-duality this afternoon?” It can never be known. But the mind wants an answer. “So why am I here in this meeting listening to this?” Well, maybe because I am particularly blessed, because I earned particularly good karma in my last life. Or maybe because I am particularly cursed by particularly bad karma in my last life. Take your pick.

Have any story you want. Each one is as good as the next one – in the sense that they’re all meaningless. But don’t expect the mind to buy that. The mind wants its stories, so the mind will go on asking “Why” questions until it gets an answer that satisfies it. When the mind gets an answer that satisfies it, it will probably stay satisfied for somewhere between three minutes and three months. And then it will look for another answer … unless it’s a very rigid mind which may be able to settle on one of the off-the-shelf answers, like one of the religions. Then it might be satisfied with that for the next 60 years.

None of the answers to the “Why” questions have any purchase other than as a story.

Louis: Can we return maybe temporarily to unconditional love… what do you mean by that or why do you mention that?

Richard: Help! Help! Help! My answer to that question… what I usually say is I don’t think the word “love” actually needs glossing, for two reasons. One is that it’s not the difficult word in that phrase. And almost everybody – apart I suppose from complete psychopaths – almost everybody has some handle on what the word “love” means. Some handle somehow.

So many things have been written and said about love… I don’t feel I’m particularly articulate. I’m not likely to be able to add anything to what’s been said by the great poets and the great spiritual thinkers. So I don’t think the word “love” is problematic. But what is problematic in that phrase is the word “unconditional”. Because to the mind, to the apparent person, love is always conditional.

The idea of “unconditional love” in a sense is an affront to the mind, because it’s a pretty harsh phrase actually. What that phrase means is that everything is included, everything is embraced by that, everything is included in love – and that includes everything that the mind most hates or most reviles or finds most distasteful. And the mind can’t get hold of that. So the mind is going to come up with an exception and say, “Well, what do you mean? What about…” And we can come up with… I’m not going to do it myself because it’s a game. But the mind could come up with something that the mind finds unpleasant in the strongest possible way and say “How can love include that? Of course it doesn’t!”

To which the answer is, “Yes, that’s what the word ‘unconditional’ means.” And that’s why it’s so difficult, because unconditional love includes everything, including that which “I” as the mind most hate. It’s very, very challenging. It’s so challenging that I am going to assert (possibly wrongly but I’m going to assert it anyway) that the mind can never get it. The mind can never get unconditional love. It might think it can and it might worry away at it like a dog at a bone, but after 40 years it still won’t have got it.

What I’m going to assert is that unconditional love can simply be seen. It can simply be seen when the mind isn’t there, or when the person isn’t there. Now when the mind hears that, if it takes it seriously, then the next thing the mind will do is go, “Okay, I’m going to work on getting myself out of the way. I, the mind, am going to get the mind out of the way, so I, the mind, can see unconditional love”. Which is complete nonsense. Although it might lie at the root of some spiritual processes, it’s complete nonsense.

Nevertheless the mind might collapse, the sense of personhood might collapse, and then there’s no need to have an argument or a discussion about ‘this’. It just becomes obvious that the nature of ‘this’ is unconditional love. That’s challenging. If you think what ‘this’ can be like, that is very, very challenging. But it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter whether it’s challenging or not, because when it’s seen, it’s seen. If it’s not seen it’s irrelevant, and when it’s seen, it’s seen.